In 2014, Virginia Energy, in cooperation with Chesterfield County and Schnabel Engineering, began work on a project at the 42 acre Mid-Lothian Mines Park aimed at improving the environment and the safety of park visitors while preserving an important part of Virginia’s history.

The park initially opened for visitors in 2004. The reclamation work to bring the park to its current state took many years and was accomplished in several phases. Today the park has exhibits depicting Virginia's coal mining history surrounded by walking trails and beautiful woodlands.

Recipient of the 2018 OSMRE Small Project Award

Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement (OSMRE) announces the winner of its 2018 Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation Small Project Award (news release). For this award, OSMRE recognizes a project that cost less than $1 million and is in a state that receives less than $6 million in Abandoned Mine Land (AML) funds. The Mid-Lothian Mines Park Project in Chesterfield County, Virginia was the recipient of this honor.

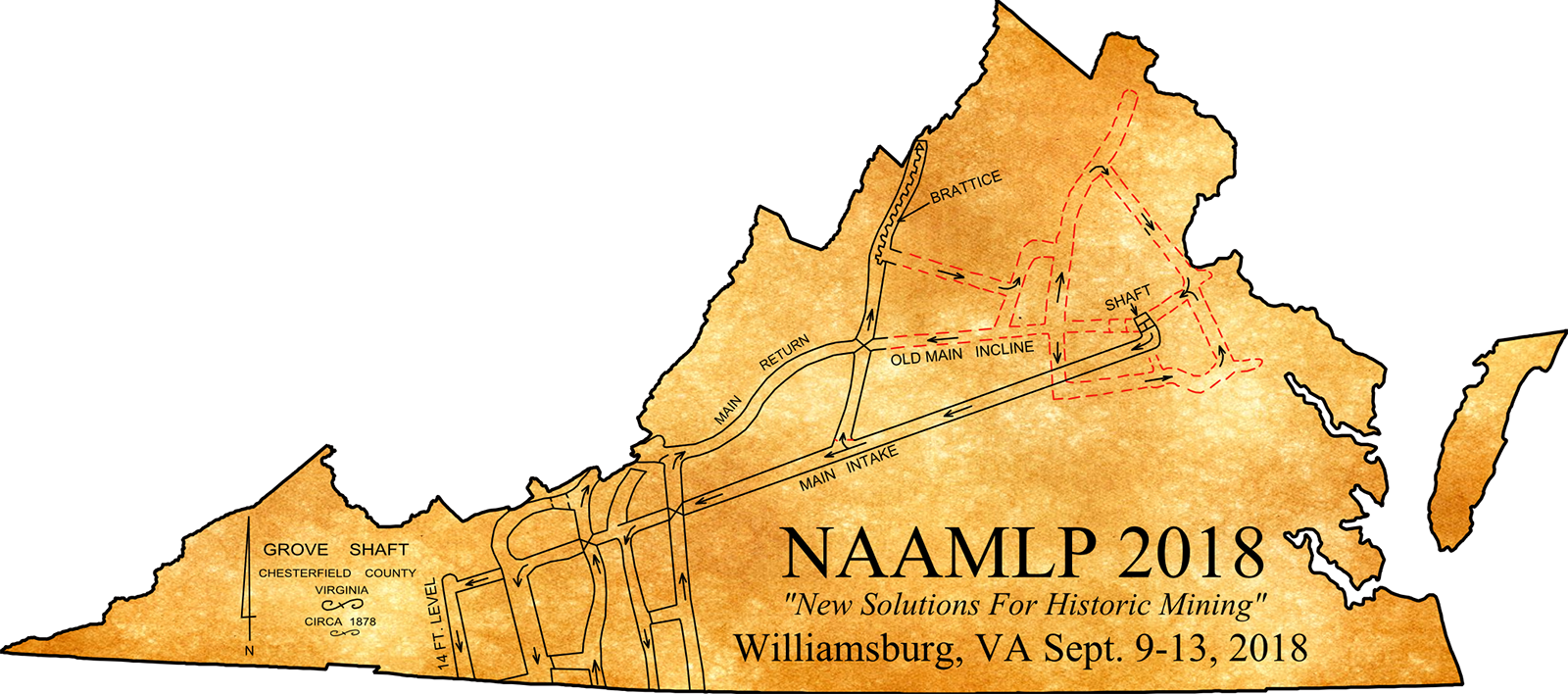

The historic Mid-Lothian Mines abandoned mine land features the remains of the first documented mining in Virginia's Richmond Coalfields. Unfortunately, the features were in serious disrepair and disintegration. Open shafts, subsidence areas and falling structures were huge safety hazards to the surrounding residential areas. After the landowner donated the land to the county, the state was able to close two vertical openings, stabilize and close two hazardous equipment and facilities structures, close one subsidence area, and stabilize two pits and three slumps. Today, the Mid-Lothian Historical Mines Park comprises the 42-acre reclamation site and is the most visited park in the county.

The history, in brief...

The Richmond Coalfield lies in a Triassic Basin that is part of a large chain of Mesozoic-aged rift basins that stretches up and down the east coast of North America, created more than 160 million years ago. Coal in Colonial Virginia was first reported by Colonel William Byrd in 1701, who noted coal occurrences on the banks of the James River near the town of Manakin (Brown and others, 1952). Coal was likely being used for domestic purposes much earlier than that by Huguenot settlers (Wilkes, 1988).

Coal was first discovered in Virginia’s Chesterfield County as early as 1701 and by 1730 coal was actively mined for commercial use. The largest concentration of mines was found in the present day Midlothian area. This was the site of first recorded commercial coal mining in North America. The earliest records of commercial coal mining in Virginia was from the mines in the Richmond basin which had begun supplying coal for local needs and expanding markets along the Atlantic coast (Brown and others, 1952). From 1748 to 1904, coal was mined nearly continuously in the Eastern Coalfields mainly from the Richmond basin, with total production estimated to be over 8 million tons (Brown and others, 1952).

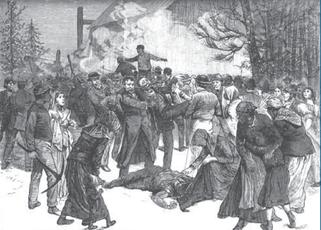

Fatal Explosion at Mid-Lothian Coal Mine,

February 3rd, 1882.

Thirty-two men were trapped in Grove Shaft.

Proximity of the coal field to the Tidewater Port was one of the major factors in commercial production efforts. Transportation of the coal from the mine sites proved to be a challenge in many ways. In the early going, coal was transported by horse and wagon to the James River. Roads were rough and much of the coal would turn to dust from jostling by the time it arrived at its destination, proving a costly expense. By 1804 the Midlothian Turnpike (present day U.S. Route 60) was developed, a vastly improved gravel surface, and the first of its kind in Virginia. At this time up to 100 wagons, each loaded with four or five tons of coal made their way to the markets. Improvements were still needed and Claudius Crozet, Virginia’s First State Engineer, surveyed the proposed route for a railroad. In 1831, the Chesterfield Rail Road, Virginia’s first rail service, was in opened. This 13 mile line was powered by beast and gravity in an ingenuous use of the sloped land and thereby reduced the cost of coal transportation to Manchester by two thirds. At one time this was reported to be the most profitable railroad in the world.

Mid-Lothian Coal Mining Company stock certificate, 1866

Courtesy of Virginia Historical Society

There were seven or eight major mines in the area by 1835 when the Mid-Lothian Coal Mining Company was chartered sitting on 400+ acres owned by the Wooldridge family. Initially, four shafts were sunk (Wood, Middle, Grove and Mid-Lothian) followed by two more (White Chimney and Rise). It was at this time the Richmond Coal Field was at its peak with production reaching 75,000 tons/year. In the mines, paid workers, both white and free blacks, were mining side-by-side with slaves (something that would have been unheard of above ground). These early miners faced many challenges including explosions and flooding. It is estimated that at least 359 men lost their lives due to explosions alone.

Tredegar Iron Works

Commercial production slowed dramatically during the War Between the States due to labor shortages. Much of this coal was used to fuel the iron furnaces that manufactured ordnance used in the war. Interesting fact: 80% of the ordnance used by the Confederacy came from the Tredegar Iron Works, just down the road from the Mid-Lothian Mines Park. At the end of the war, George Wooldridge’s Confederate dollars became worthless and the company borrowed money from the Burrows family of New York to explore for additional deposits. They dug and bored the Sinking shaft to 1352 feet, just shy of where the coal was later found, before running out of funding. The result is the company went bankrupt and was sold to its New York financier at auction.

Coal was mined at Midlothian until the 1930s under The James River Coal Corporation and the Murphy Coal Corporation. The land and its rich history were donated to Chesterfield County in 2004 for a park.

A Compilation of the History Coal Mining in Henrico County, VA prepared by Dave Garlock summarizes other researcher's work highlighting the people, places, events, and timeline related to the two hundred years of coal mining operations in Henrico County. The Compilation contains the work of many researchers, historians, geologists and newspaper reporters from which this author has attempted to combine the key elements into a coherent presentation. This author has also conducted research to include maps and photographs to illustrate the past.

The reclamation effort ...

Two hundred years of coal mining activity left abandoned shafts, portals, and mining structures as reclamation was unheard of at the time. Though Richmond was a well-populated city, the mining districts fringed the outskirts of town. Each type of mining (pits, slopes, shafts) has left a different type of abandoned feature on the ground surface. Some of the shafts that remained open filled with water, other pits and shafts have seemed to heal over and reclaim themselves. It is these that can pose the greatest danger: these features seem to be just depressions in the ground, but may be shafts that have “false bottoms” where years of leaf and tree litter have obscured the opening. These features posed a serious danger to the public as homes encroach upon the mine sites.

In 2012, Chesterfield County and Merricks Construction, Inc. erected an exact replica of the original headstock at the Middle Shaft Mine, one of 4 mines orginiating from 1836 by Mid-Lothian Mining and Manufacturing Company.

Virginia Energy helped fund a $2 million dollar transformation of Abandoned Mine Land (AML) features for the restoration and reclamation of the Mid-Lothian Mines Park in collaboration with the Mid-Lothian Mines and Rail Roads Foundation, VDOT, DEQ and others. Several features remained on the site, including the ruins of the Grove Shaft (circa 1835-1870 and possibly the oldest standing coal mining structure in the country), abutments, and plenty of ponds, pits, subsidence, and other hazards.

Initially two features were reclaimed within the park: the entrance to the Murphy slope and the air shaft for the Murphy slope. At the time of this reclamation, the landowner did not wish us to reclaim the other features. It was later the land owner donated the property to the county for the purpose of creating this park.

A memorandum of understanding was signed in 2010 clarifying the work to be done and the responsibilities of both DMLR and Chesterfield County. we paid 75% of the cost of exploration, compliance and reclamation. The County was responsible for aesthetics such as trail improvements, signs, and public facilities.

The reclamation was done in several phases:

- Phase 1 was the exploration including environmental and archeological impact studies which was funded both by Virginia Energy ($170,547) and Chesterfield County. DEQ and the Chesterfield Fire Department conducted exploration of the Grove Shaft using underwater video equipment provided by DEQ.

Footage captured by Brad White of DEQ with an underwater camera.

A 19th century pulley wheel was discovered about 50 feet below the water surface.

- Phase 2 was the Reclamation and Construction including improvements such as an access road and bridge including meshing, grouting, and fencing. Grove Shaft and Grove air shaft were capped with wire mesh. Subsidence was grouted. Virginia Energy provided $391,649.94 in AML funding for this effort.

A 19th century pulley wheel was found in the Grove Shaft. This 625-foot shaft was pumped down to 50 feet in order

to retrieve the wheel that was identified when DMME shot the underwater footage.

- Phase 3 include interpretive signs, public facilities, parking, etc. DMME provided $412,092.12 in AML funding.

Signage showing original Grove Shaft Ventilation Building, c 1924.

Grove Shaft ruins present day.

The park is open to visitors now and has been reported as being the most visited of all parks in Chesterfield County.

Mid-Lothian Mines Park today

Acknowledgements ...

Gerry Wilkes, Virginia Energy

at Mid-Lothian Mines Park, Chesterfield County

Virginia Energy's Gerry Wilkes worked tirelessly on this project for many years. He retired in 2017. The success of this massive project is a result of his dedication and hard work.

Paul Saunders, Mineral Mining Mine Permitting Supervisor

Phil Skorupa, Mineral Mining and Gas and Oil Director, and

Butch Lambert, Retired Deputy Director

Peppy Jones, Executive Director of the Mid-Lothian

Mines and Rail Roads Foundation

Special thanks also to Schnabel Engineering's Kenneth Megginso and DEQ's Brad White for their contributions to the success of this effort.

And to Chesterfield County's Executive Director of the Mid-Lothian Mines and Rail Roads Foundation, Peppy Jones, whose family was some of the earliest owners of the Coalfields Station and whose gift of oratory vividly recreates the history of the site.

Learn more about Historic Mining in Virginia :

Mining in Virginia has taken place in one form or another since man’s initial habitation of the land. Over 50 minerals have been mined in Virginia, contributing greatly to the state’s economy but also sometimes causing adverse impacts on the public’s health and safety, and the environment.

Virginia's Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Program, administered by the Division of Mined Land Reclamation, was established in the late 1970s to correct pre-Federal Act (1977) coal mine related problems adversely impacting public health, safety, general welfare, and the environment.

2006 legislation requires that the seller of any new dwelling in Planning District 15 disclose in writing to the purchaser whether they have knowledge of previous mining on the property, or the presence of abandoned mines, shafts, or pits. In an effort to assist property owners, DMME provides a series of maps depiciting known locations with abandoned mine land features.

Coal Mining Today

Coal deposits occur in three main regions in Virginia: the Southwest Virginia Coalfield, Valley Coalfields, and the Eastern Coalfields.

Virginia’s coal miners reported production of about 12.8 million short tons of bituminous coal in 2017. Of the nation’s twenty-five coal-producing states that reported domestic production totaling 774 million short tons in 2017, Virginia ranked twelfth with a 1.7 percent share of the total.

Whisonant, R.C., 2000, Geology and history of the Confederate coal mines in Montgomery County, Virginia: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Virginia Minerals, v. 46, no. 1, 8 p.

Wilkes, G.P., 1988, Mining history of the Richmond coalfield of Virginia: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Publication 85, 51 p.