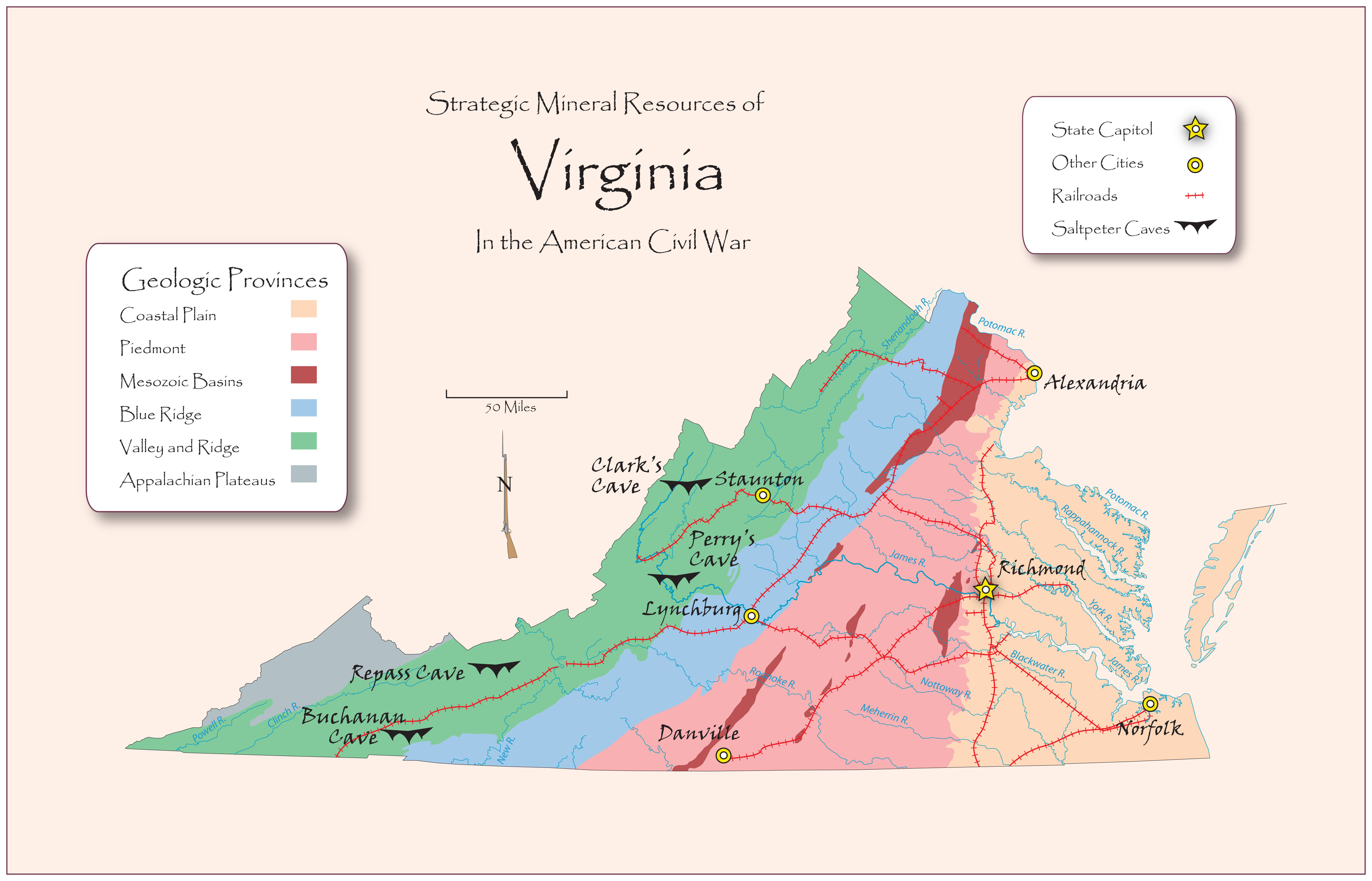

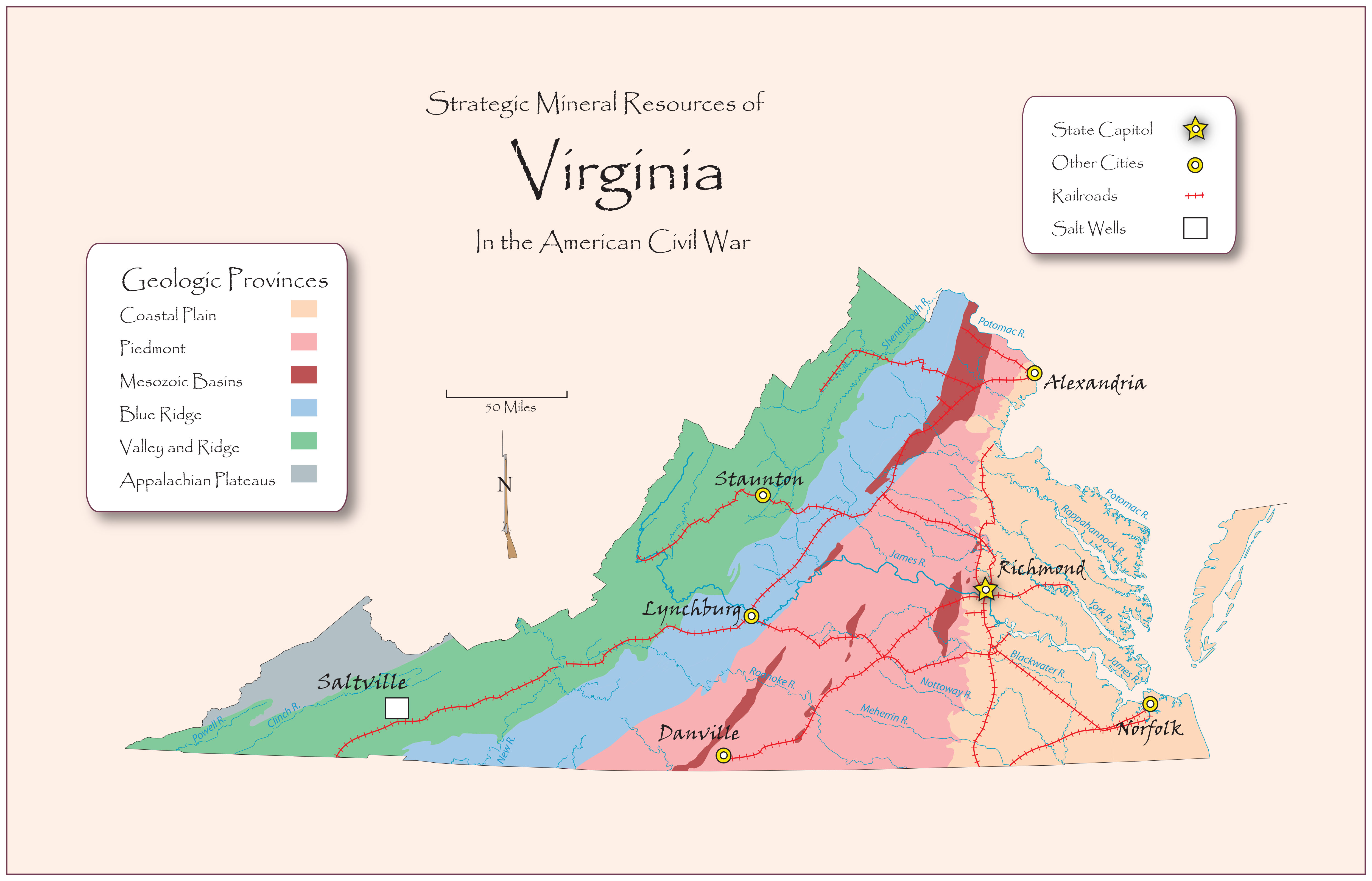

The American Civil War was a conflict where natural resources were a central strategic objective. From the opening shots, the North made efforts to deny the South the materials necessary to carry on the fight. Of all the states in the Confederacy, Virginia was the richest in developed natural resources, and as the fighting escalated the South relied heavily on Virginia in what became a war of commerce. As the blockade of Southern ports took its toll, Virginia became the chief supplier of iron, lead, and salt throughout the South. Virginia was also a major producer of coal and niter. All of these items were crucial to the war effort.

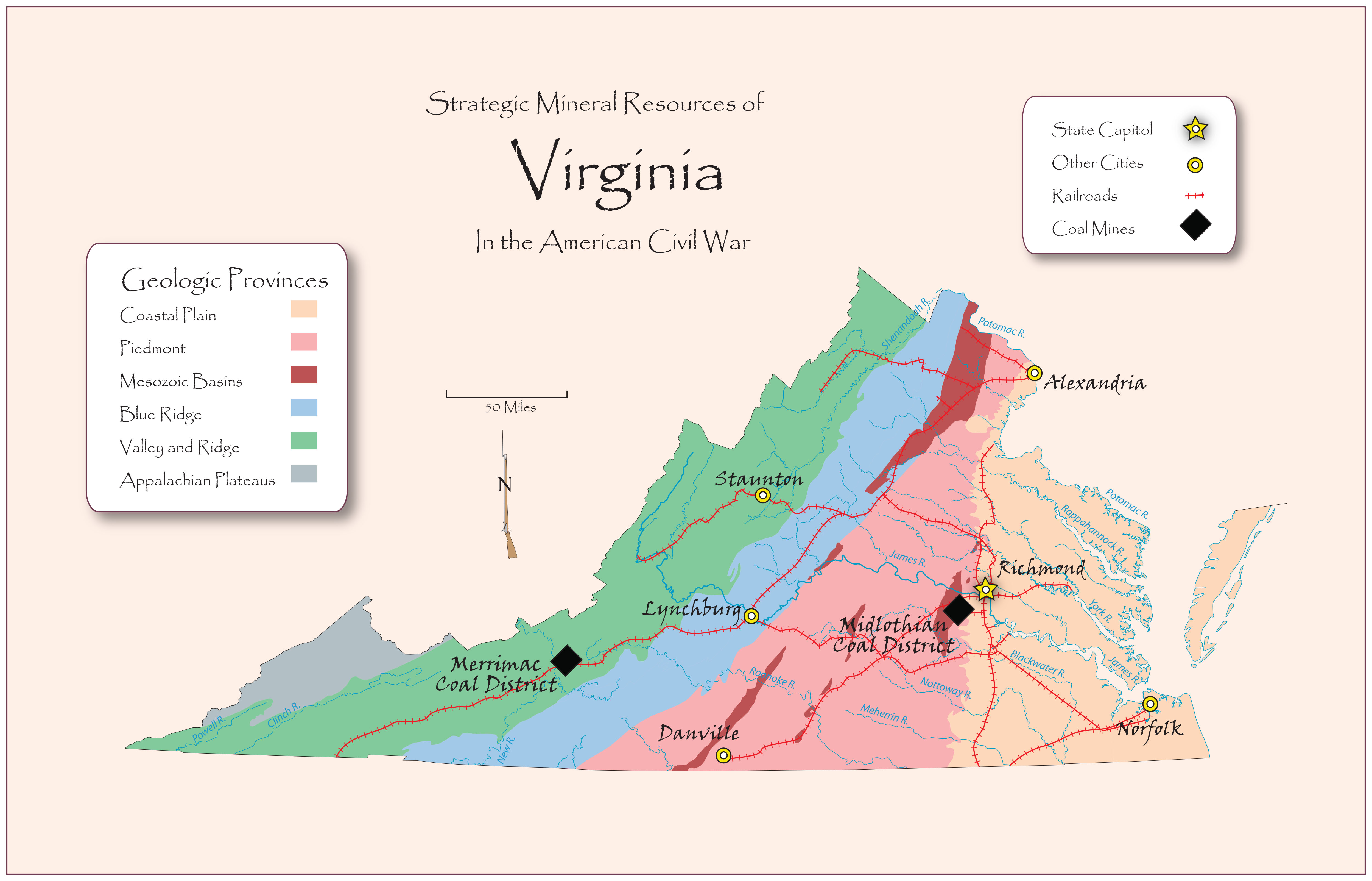

Sometime around 1700, coal was discovered in the Huguenot Springs area west of present day Richmond. This coal was used in local blacksmith forges and may have been the first coal mined in the Western Hemisphere. Eventually six mining districts were established in the area: Huguenot Springs, Manakin, Midlothian, Deep Run, Carbon Hill, and Clover Hill.

The coal was initially deposited as layers of peat in a fault-bounded basin, which slowly filled with Triassic-age swamp and lake sediments. The swamps and lakes were eventually buried by sand and silt, and the peat was converted to coal.

In 1758, nine tons of coal from the Midlothian mines were shipped to New York City, the first recorded commercial production in the Colonies (Wilkes, 1988). During the American Revolution, Midlothian coal supplied the cannon foundry at Westham. Initial production was modest, on the order of 1,000 tons annually, but the Richmond coal market expanded considerably when the Federal Government imposed an import tariff on foreign coal in 1794 (Wilkes, 1988). From the late eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth century, the streetlights of New York, Philadelphia, and Boston were lit with gas derived from Richmond coal.

Stock certificate for the Mid-Lothian Coal Mining Company from www.midlomines.org.

The mining around Richmond spawned a flurry of advances in transportation. The Manchester & Falling Creek Turnpike opened in 1804, and by 1807 it was the first graveled roadway of any length in Virginia (O’Dell, 1983). Around 1824, this turnpike was carrying from 70 to 100 wagons daily, each with four or five tons of coal, totaling more than 40,000 tons annually (Coleman, 1954). In 1828, a canal was opened along Tuckahoe Creek, linking the Manakin mines to the James River. The Railroad, completed in 1831, running twelve miles from the Midlothian mines to wharves on the James River, was the first railroad built in Virginia. In 1836, the Chesterfield Railroad reported carrying 25,903 cars with 84,976 tons of coal during the year (Coleman, 1954), and boasted that it was the most profitable railroad in the world.

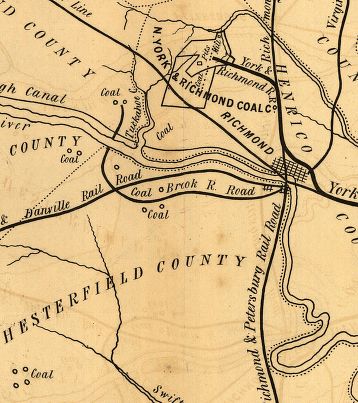

Coalfields around Richmond, Virginia, 1856. From the Library of Congress

During the Civil War, most of Virginia’s coal supply was used to fuel railroad locomotives, with the remainder allocated for iron manufacture. The Confederate Army commandeered the Black Heath Mine in the Midlothian District, and this coal was used for making cannons at the Tredegar Iron Works. Coal from the Carbon Hill and Clover Hill districts was also used at Tredegar. Semi-anthracite coal from the Merrimac District mines near Blacksburg is believed to have fueled the engines of the CSS Virginia, the Confederacy’s first ironclad warship. These mines were operated by the Confederate Government and produced coal for manufacturing salt kettles and for making shot and shell at Howardsville on the James River (Whisonant, 2000).

During 1861 and 1862, total Virginia coal production amounted to 445,000 tons, but from 1863 through 1866 total production dropped to a mere 40,000 tons, primarily due to lack of laborers (Boyle, 1936). In May of 1864, when Union cavalry under General August Kautz raided the Midlothian area, Major Samuel Wetherill, a miner from Pennsylvania, intervened to rescind the orders to set the coal mines afire.

The U.S. Census for 1870 shows that Virginia produced 61,803 tons of coal that year, indicating that the industry was slowly recovering after the war. At this time, the great coalfields of far southwestern Virginia had yet to be exploited.

References:

Boyle, Rockwell S., 1936, Virginia’s mineral contribution to the Confederacy: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Bulletin 46, p. 119-123.

Coleman, Elizabeth Dabney, 1954, Forerunner of Virginia’s first railway: Virginia Cavalcade, Winter, p. 4-7.

O’Dell, Jeffrey M., 1983, Chesterfield County: Early architecture and historical sites: Chesterfield County Board of Supervisors.

Whisonant, Robert C., 2000, Geology and history of the Confederate coal mines in Montgomery County, Virginia: Virginia Minerals, v. 46, no 1.

Wilkes, Gerald P., 1988, Mining history of the Richmond coalfield of Virginia: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Publication 85.

During the American Civil War, iron provided the raw material for pistols, rifles, cannons, land mines, sabers, and knives, as well as railroad locomotives and ironclad warships powered by steam. Iron provided not only bayonets and bridles, but also skillets, cauldrons, canned rations, axes, saws, shovels, chains, surgeon’s tools, and countless pieces of miscellaneous hardware. There were perhaps as many as five million horses and mules engaged in the conflict, requiring twenty million iron horseshoes. During this time, iron re-defined warfare, top to bottom.

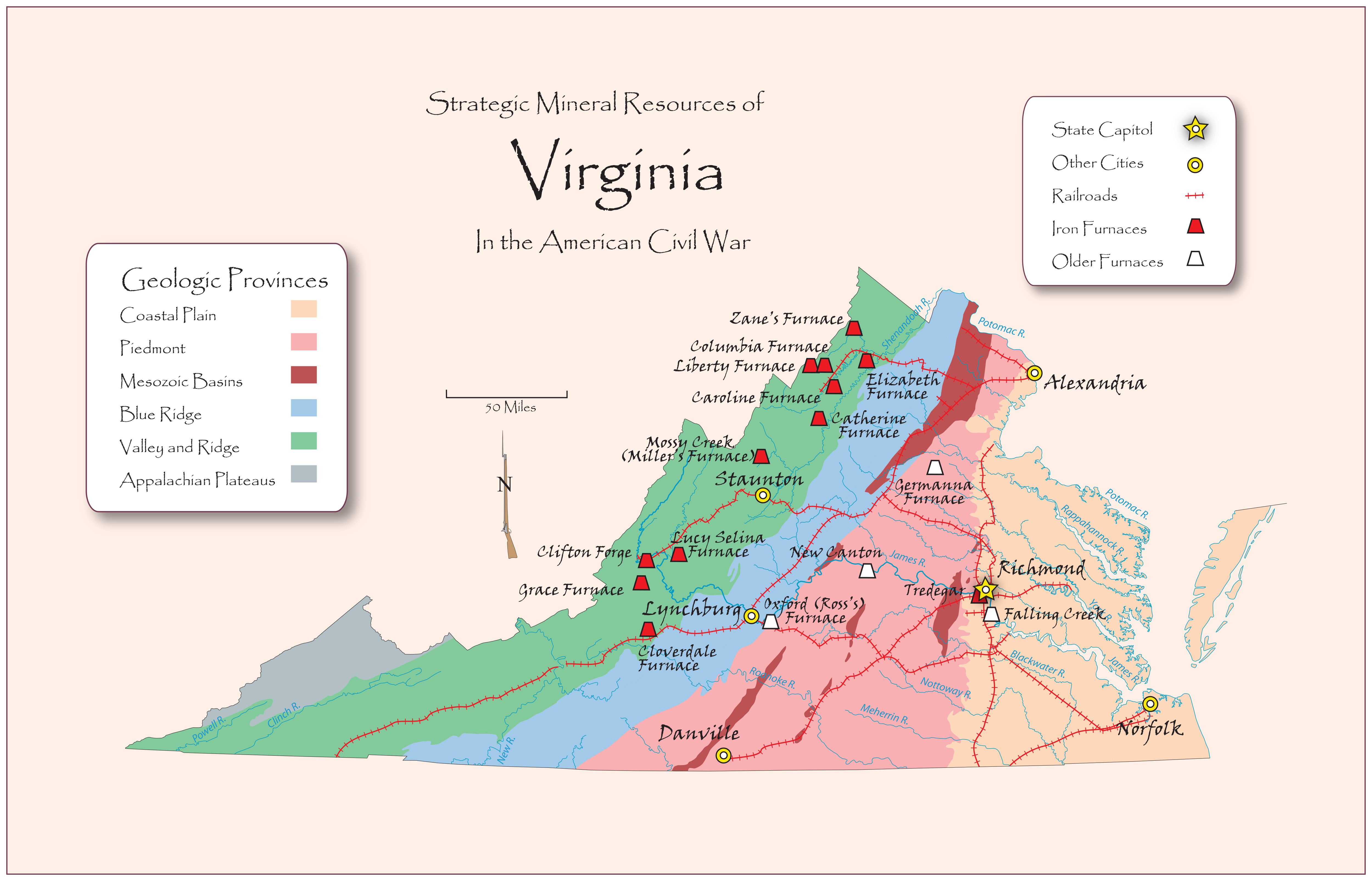

At the beginning of the Civil War, Virginia and Tennessee were the only significant iron producing states in the South. Tennessee was overrun early in the fighting, so without Virginia’s iron the Confederacy would have been absurdly overmatched. Virginia’s iron industry managed to produce until the end of the war, despite being caught in the midst of the combat.

Iron occurs as a variety of minerals across the state of Virginia, but mining operations prior to the Civil War exclusively used a type of ore known as limonite. Limonite is a hydrated iron oxide with a general formula FeO(OH)·nH2O, commonly a byproduct of the weathering of iron-rich sulfide or silicate minerals.

Iron mining in Virginia began shortly after the establishment of the Jamestown settlement, in 1619, when the first iron furnace in English America was built on Falling Creek, a few miles south of present-day Richmond. Only a few test runs had been completed when the facilities were destroyed during the Powhatan Indian uprising of 1622. Falling Creek, as well as several other ensuing iron operations on Virginia’s Coastal Plain were exploiting a type of limonite known as bog ore, which forms when iron-rich groundwater emerges from springs into bogs or swamps and the iron precipitates as it is oxidized. These early operations on the Coastal Plain were poor producers and short lived.

Much later, in 1716, Alexander Spotswood established Germanna Furnace about five miles west of Fredericksburg, and in the next several decades other iron operations sprang up in the vicinity. These furnaces were using ore from the Gold-Pyrite Belt, a swath of rocks extending down the Piedmont from Prince William County on the north to Buckingham County on the south, rocks that contain abundant pyrite (iron sulfide, FeS2) that has weathered into limonite. This type of ore is known as gossan and results from the intense oxidization and leaching of sulfide deposits that are believed to have originally formed by submarine volcanic-hydrothermal processes (Good, 1981; Duke, 1983). The Gold-Pyrite Belt was an important producer in Colonial days, but lost significance as richer ores were developed further inland.

Further west on the Piedmont lies another ore belt, roughly coinciding with the valley of the James River from below Lynchburg northeastward. Here, the limonite is concentrated as residual deposits resulting from the deep weathering of beds of limestone (Furcron, 1935). This district was a leading Virginia iron producer in Thomas Jefferson’s time.

During the American Revolution, Virginia’s iron industry made a significant contribution to the war effort. The New Canton mines in Buckingham County opened during the war, and Jefferson reported that Ross’s Furnace in Campbell County was making 1,600 tons of pig iron annually. Meanwhile, to the west of the Blue Ridge, Miller’s Furnace in Augusta County and Zane’s Furnace in Frederick County each made about 600 tons (Jefferson, 1785). A cannon foundry operated on the banks of the James River at Westham, but in January of 1781 Benedict Arnold’s British Cavalry ransacked the facility, dumping the equipment into the river.

Virginia’s premier limonite iron ore, the so-called Oriskany ore, is found in the Valley and Ridge Province. Typically the iron occurs where a thick shale bed containing disseminated pyrite overlies limestone. The iron weathers from the pyrite into an acidic solution that percolates downward into the pores of the limestone, where the dramatic change in pH causes it to precipitate as limonite (Gooch, 1954). Ore bodies range from small, isolated pockets to 700-foot-long porous masses. Well developed Oriskany deposits occur in the Great North Mountain area in Shenandoah County, in Massanutten Mountain, and in the Clifton Forge District straddling Alleghany, Bath, Botetourt, and Craig counties. This type of ore was heavily utilized in charcoal furnaces before, during, and shortly after the Civil War, and was considered relatively high grade at the time.

Another major source of limonite in the Valley and Ridge occurs as shallow residual clay deposits, sometimes known as “mountain ore.” The iron occurs as a coarse grit and lumps scattered throughout massive layers of remnant clay that formed by the thorough weathering of a considerable thickness of impure limestone. Groundwater removed much of the original limestone, leaving a thick residue of clay and further concentrating the iron. This type of ore is found in a swath thirty miles long and three miles wide that straddles Pulaski, Wythe, and Smyth counties in southwestern Virginia. Some ore bodies occupy continuous tracts of several acres. “Mountain ore” deposits were extensively mined from the 1760s to 1907, and in Virginia were second only to Oriskany ores in importance.

During the early decades of the new nation, Virginia had the third highest pig iron output of the United States, trailing only New York and Pennsylvania. Many furnaces in Virginia came into blast at this time, exploiting Oriskany-type deposits along the western margin of the Great Valley, particularly in the Shenandoah District (Columbia Furnace, 1810; Liberty Furnace, 1817; and Taylor Furnace, 1845), and the Clifton Forge District (Lucy Selina Furnace, 1827; Roaring Run Furnace, 1832; Clifton Furnace, 1846; Dolly Ann Furnace, 1848; and Grace Furnace, 1849). By 1840, Virginia had forty-two furnaces producing 18,810 tons of iron annually (U.S. Census, 1840).

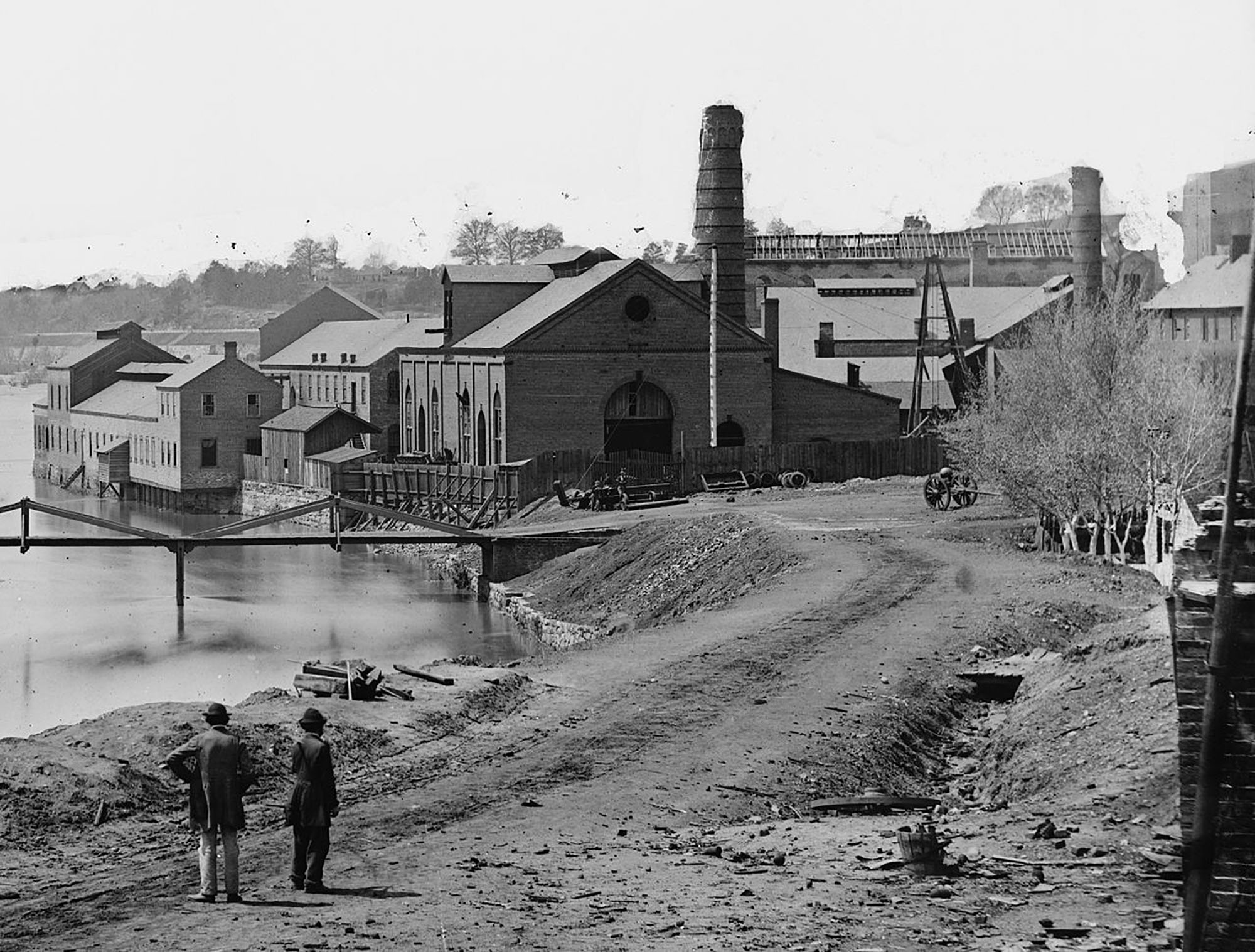

Tredegar Iron Works, 1865, photo by Alexander Gardner

However, about this time the economy and the political stature of the Old Dominion began to wane. Virginia’s industry lagged behind the rapidly expanding Northern industry, which was geographically blessed with abundant coal and readily available water power. In 1850, Virginia’s iron production had fallen to seventh in the nation, and now trailed Tennessee in the South. The annual value of iron manufactured in the state had dropped precipitously from $528,249 produced by thirty-four furnaces in 1850 to $308,173 from sixteen furnaces in 1860, on the eve of the war.

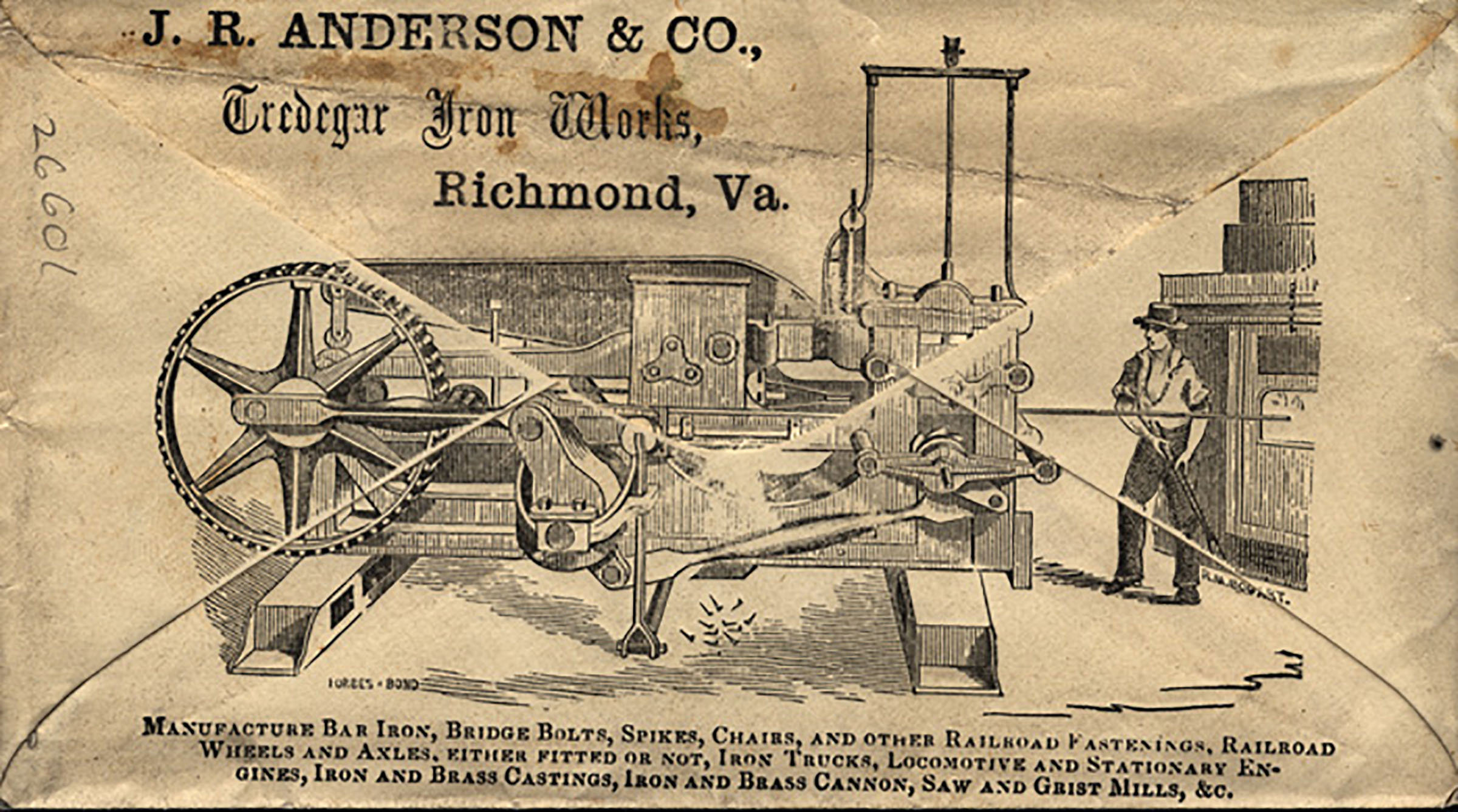

When the fortunes of history swept Virginia into the Civil War, the state’s iron industry had to revive from its stupor. The Confederacy would need to rely heavily on the Tredegar Iron Works on the north bank of the James River in Richmond. When the war’s first shots were fired on Fort Sumter, Tredegar was the nation’s third largest iron manufacturer, specializing in heavy ordnance and a complete line of railroad products including locomotives, freight cars, wheels, axles, spikes, and even iron bridges (National Register of Historic Places). In addition they made steam engines for ships and sugar mills. The furnaces were supplied with pig iron carried by horse drawn canal boats plying the James River and Kanawha Canal. The first shot, incidentally, came from a 10-inch mortar manufactured at Tredegar.

As Tredegar geared up for the war, Virginia’s iron mines were unable to generate sufficient pig iron, and the facility operated at only one-third capacity (Brady, 1991). Tredegar’s owner, Joseph Anderson, remarked in a July 1862 letter (cited in Dew, 1966), “Everything must stop unless we go into the mountains and purchase and operate blast furnaces to make pig iron.” Anderson, with financial help from the Confederate government, managed to acquire ten furnaces west of the Blue Ridge (Brady, 1991). Four of them — Cloverdale, Grace, Glenwood, and Columbia — were in blast when acquired. Five of them — Australia, Caroline, Catawba, Rebecca, and Jane — needed repairs, while Elizabeth Furnace was ultimately too near to Union Army activities and was not brought back on line. Anderson had to find competent managers, acquire teams and wagons for hauling ore and pig iron, and provide food for hundreds of furnace laborers who rebuilt stacks and replaced machinery at furnaces long out of blast (Dew, 1966).

The Oxford Furnace, formerly the Old Ross Furnace, produced iron during the war, and the Confederate Government worked the mines at Bremo Bluff opposite New Canton (Furcron, 1935). Furnaces in southwestern Virginia supplied Tredegar. Operations in Wythe County using “mountain ore” included the Wythe Furnace, Raven Cliff, Grey Eagle, Graham/Cedar Run, and Graham/Barren Spring. The Thomas Ironworks in Smyth County also supplied Tredegar.

Envelope advertising Tredegar iron products

from the Library of Congress

During the war, the Tredegar Iron Works became the single most important iron operation in the Confederacy. At its peak, Tredegar consisted of two rolling mills capable of producing 14,000 tons of bar and sheet iron annually, along with two gun foundries capable of casting cannon ranging from small mountain howitzers to 10-ton coastal defense guns. There was an ammunition foundry for making cannon balls and boring mills for reaming gun barrels. There was a machine shop, a boiler shop, and a locomotive factory, as well as ancillary brass and copper shops, carpenter shops, blacksmiths, a company store, office buildings, and housing for the slaves (National Register). Tredegar turned out a total of 1,099 artillery pieces during the war, about half of the South’s entire production (Boyle, 1936). Tredegar also manufactured steam locomotives and rails, as well as 723 tons of iron plate armor for the CSS Virginia, the Confederacy’s first ironclad warship (Nelson, 2004). Prototypes for the modern submarine, torpedo, and machine gun were developed here.

Union forces targeted several Virginia furnaces during the war. The Elizabeth and Caroline furnaces in Massanutten Mountain were torched and Columbia Furnace was ransacked three times. Grace Furnace was demolished by General David Hunter’s troops in June of 1864. Thomas’ Ironworks in Smyth County and Barrett’s Foundry in Wythe County were destroyed during General George Stoneman’s devastating raid in December of 1864. Yet despite constant depredations, as late as November 1864, Virginia still had eighteen operating iron furnaces (Boyle, 1936). “Quite possibly,” says Civil war historian Charles P. Roland, “the tenacity of Confederate authorities in fighting for Richmond was stiffened as much by the need for holding the Tredegar Works as for protecting the seat of government.” (Roland, 1960)

Tredegar avoided significant damage during the burning of Richmond and returned to production at the end of 1865. [Anderson hired fifty armed guards to fend off the arsonists detailed to keep valuable military items from falling to the enemy.] By 1873 it was operating at twice its prewar capacity, and later went on to supply munitions to the United States military during the Spanish American War, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War.

References:

Boyle, Rockwell S., 1936, Virginia’s mineral contribution to the Confederacy: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Bulletin 46, p. 119-123.

Brady , T. T., 1991, The charcoal iron industry in Virginia: Virginia Minerals, v. 37, no. 4.

Dew, Charles, 1966, Ironmaker to the Confederacy, Joseph R. Anderson and the Tredegar Iron Works: Yale University Press, New Haven.

Duke, N.A., 1983, A metallogenic study of the central Virginia gold-pyrite belt: Ph.D. dissertation, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg.

Furcron, A. S., 1935, James River iron and marble belt: Virginia Division of Geology, Mineral Resources Bulletin 39.

Gooch, E. O., 1954, Iron in Virginia: Virginia Division of Geology, Mineral Resources Circular No. 1.

Good, R. S., 1981, Geochemical exploration and sulfide mineralization, in Geologic investigations in the Willis Mountain and Andersonville quadrangles, Virginia: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources Publication 29.

Jefferson, Thomas, 1785, Notes on the State of Virginia: Paris.

Nelson, James L., 2004, Reign of iron: William Morrow, New York.

Roland, Charles P., 1960, The Confederacy: University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois

U.S. Census, 1840, Washington D.C.

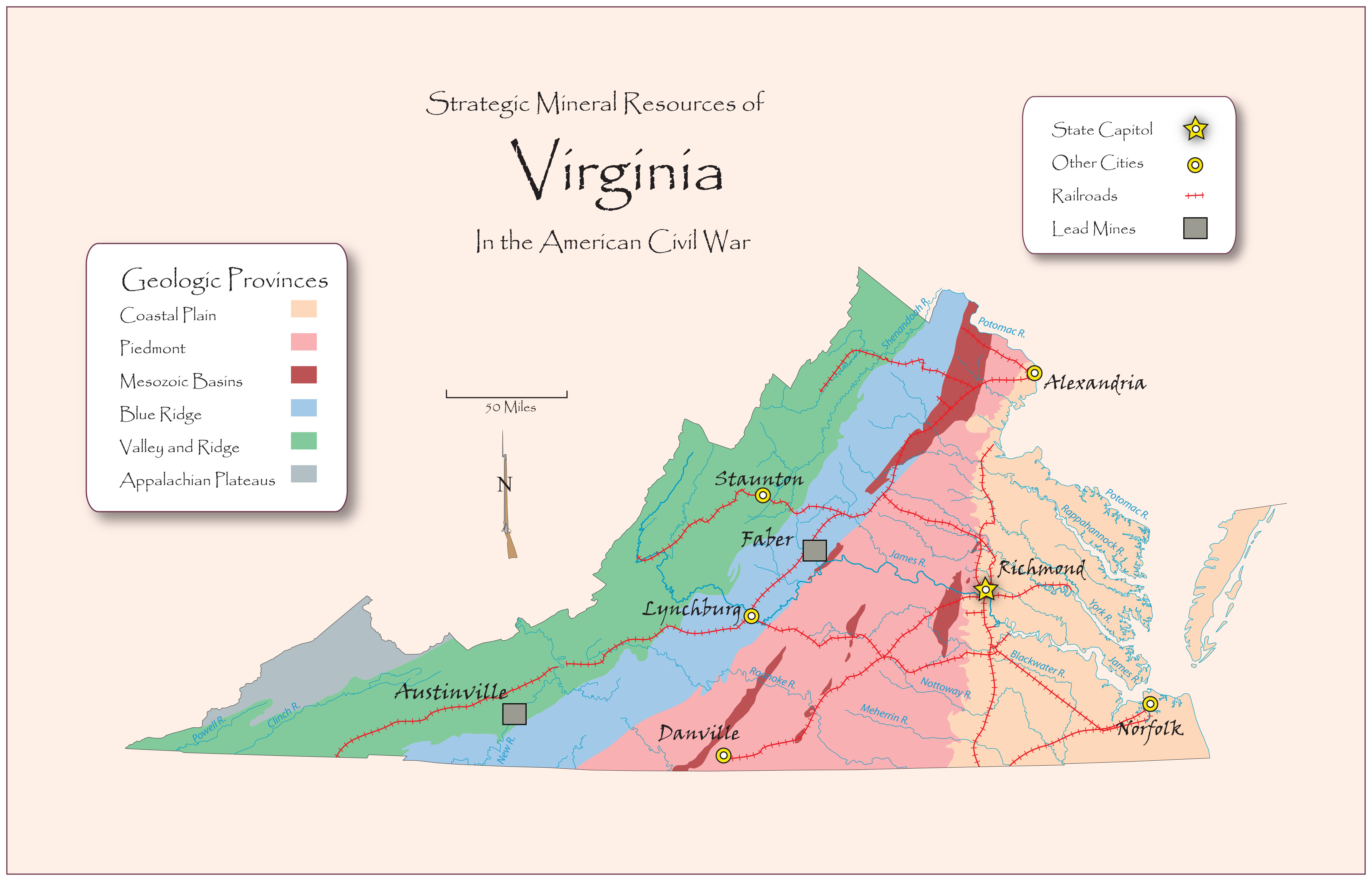

Because of lead's high density and low melting point, it is ideal for making bullets, and the lead mines at Austinville in southern Wythe County were the primary source for Confederate ammunition (Whisonant, 1996). These deposits occur as lenses of the sulfide minerals galena, sphalerite, and pyrite within the Cambrian-age Shady dolomite. These are typical "Mississippi Valley" type deposits resulting from warm, metal-rich brines permeating into breccias zones in carbonate host rocks, which, in this case are sliced up by multiple, imbricate, steeply inclined thrust faults and associated fractures (Sweet et al., 1989).

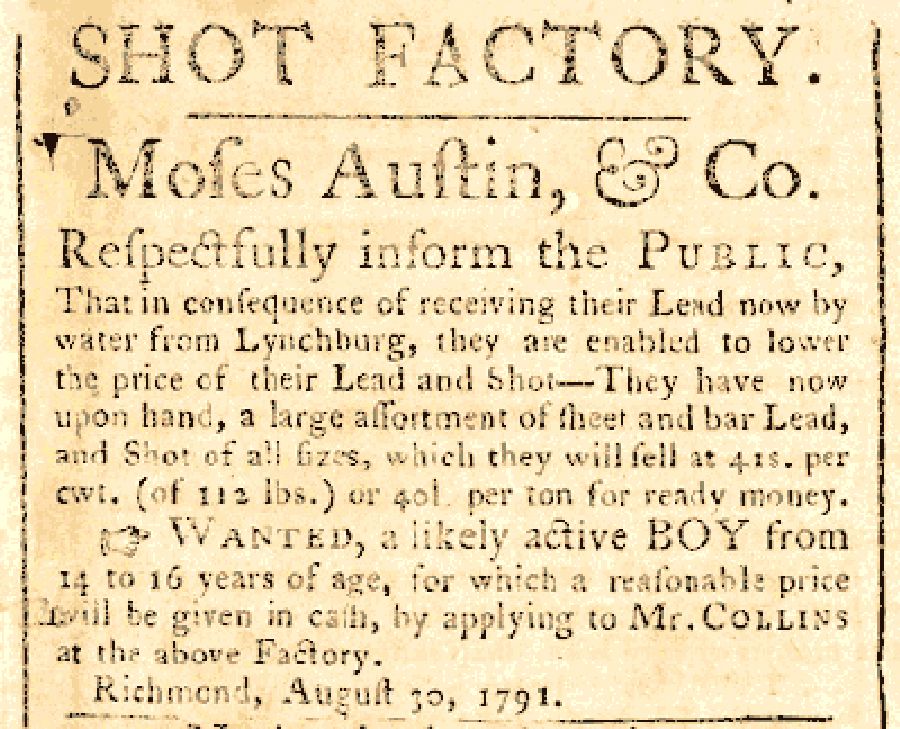

Newspaper advertisement for lead

and shot from Austinville. From

the Virginia Gazette & General

Advertiser, Richmond 1791.

In 1756, Colonel John Chiswell, a British colonial officer, discovered lead along the New River in what is now Wythe County, Virginia. Chiswell staked his claim and imported a Welsh miner named William Herbert to manage the enterprise, which supplied ammunition to the American colonies during the French and Indian War. However, in 1776 mining was temporarily curtailed and the property was confiscated by a Revolutionary Army detail under orders from General Washington. In 1789, the mines were sold at public auction to Stephen and Moses Austin; the latter was the father of famous Texan Stephen F. Austin. The Austin brothers ran the mine until 1805, when they defaulted on the payment and the property again reverted to the State of Virginia, which sold it to a group led by Thomas Jackson. It is not known exactly who built the shot tower or when, although it is likely that it was completed by Jackson sometime between 1807 and 1812. Mining was hampered by multiple ownership, but in 1848 the various interests were bought out and the Wythe Union Lead Mine Company was formed. From 1838 to 1848 the mines produced 6,511,450 pounds of lead valued at $146,577.07 ($45.02 per ton). From 1848 to 1858 the company claims to have produced 7,613,334 pounds valued at $241,178.72 ($63.35 per ton) (Watson, 1905).

During the Civil War, the Wythe County mines were the primary source of lead for bullets for the Confederacy, augmented by scavenged plumbing and window weights, and spent ammunition scoured from battlefields. About 3,300,000 pounds of lead were produced at the Austinville mines during the war.

Union raiders made forays into southwestern Virginia in July of 1863 and May of 1864, but failed to reach the mines. However, on December 17, 1864, General George Stoneman’s cavalry succeeded, and set fire to the mine offices, storehouse, and stables while destroying the crushing machine, bellows, and furnaces. Despite the damage, the mines were back in operation by March 22, 1865 (Whisonant, 1996). Stoneman returned April 7, 1865, at the time of the Confederate collapse, and ransacked the partially rebuilt facility.

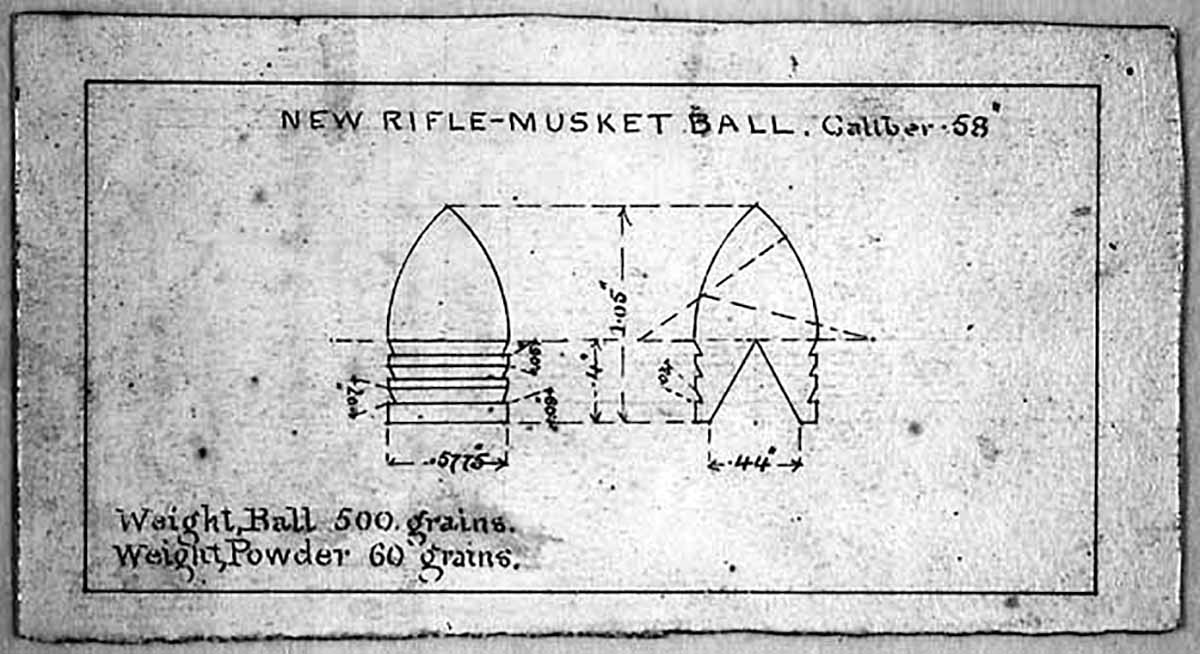

Diagram of .58 caliber ammunition specifications. From the

Smithsonian, Neg. #91-10712: Harpers Ferry NHP Cat. #13645.

One other Virginia historic mining operation, the Faber mines in Albemarle County, also supplied lead to the Southern war effort. Discovered in 1849, this deposit is a vein/shear zone containing silver-bearing galena and sphalerite. The Faber mines were worked intermittently, and in the end the Confederate government received only 7,204 pounds of lead (Watson, 1905). The miners fled when Union General Philip Sheridan's cavalry crossed the Blue Ridge in March of 1865 and severely damaged the facility.

The Wythe County mines reopened shortly after the war, and remained in operation until 1981, closing after 225 years of almost continuous production. Over this period, it has been estimated that the district produced 34 million tons of ore (Miller, 1985). The shot tower, one of only three remaining in the United States, is now the centerpiece of Shot Tower State Park.

References:

Miller, J. W., 1985, Statistical modeling of Austinville Mine: a guide to exploration: Phd. dissertation, University of Georgia.

Sweet, P. C., Good, R. S., Lovett, J. A., Campbell, E. V. N., Wilkes, G. P., and Meyers, L. L., 1989, Copper, lead, and zinc resources in Virginia: Virginia Division of Mineral Resources, Publication 93.

Watson, Thomas L., 1905, Lead and zinc deposits of Virginia: Geological Survey of Virginia, Bulletin 1.

Whisonant, Robert C., 1996, Geology and the Civil War in southwestern Virginia: the Wythe County Lead Mines: Virginia Minerals, v. 42, no. 2.

Niter is the mineral form of potassium nitrate, KNO3, also known as saltpeter, commonly found as massive encrustations and effervescent growths on cave walls, ceilings, and floors. Along with sulfur and charcoal, niter is an essential ingredient in gunpowder.

Virginia caves are known to have been worked for saltpeter as early as 1740 (Faust, 1964) and they supplied niter for gunpowder during the American Revolution and the War of 1812. Production figures are almost non-existent, although the 1810 U.S. Census did report that Virginia provided 59,175 pounds of saltpeter that year. During the ensuing decade, consumption increased drastically due to frontier fighting, subsistence hunting, government military requirements, and the use of explosives in mining and construction of roads and canals (Faust, 1964). Apparently the increased demand was not matched by domestic production, as Virginia, along with the rest of the Southern states, imported most of their gunpowder in the years leading up to the Civil War.

In 1862, as the Federal naval blockade began to curtail foreign imports, the Confederate Government set up the Nitre Corps, which soon expanded into the Nitre and Mining Bureau. One of the bureau’s principle missions was to find and develop nitrate caves. It has been estimated that twenty-five caves in Virginia produced saltpeter during the war (Powers, 1981), among them Buchanan Saltpeter Cave in Smyth County, Perry’s Saltpeter Cave near Eagle Rock, Repass Cave near Bland, Trout Cave near Franklin (now in West Virginia), probably Sinnet Cave south of Franklin, and most likely Clark’s Saltpeter Cave — one of the longest-producing caves in the region — near Fort Lewis. The majority of operations were small, but by using basic procedures three men could produce 100 to 200 pounds of saltpeter in three days (Powers, 1981). Records of mining activities are scarce and it is not unusual for the names of caves to change. In addition, this was largely a cottage industry — the caves were usually worked by mountain folk from small farms with no slaves and who were only marginally loyal to the Confederacy, resulting in “a notoriously unreliable work force where absenteeism and desertion were common” (Whisonant, 2001).

Saltpeter operations were widely scattered and difficult to locate, so they were not principal military targets, although they were occasionally assaulted by Federal raiders. General William Averell, on his way to tear up the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad in December 1863, disrupted the mining operations near Mountain Grove in Bath County. During the first week in March 1864, the 12th New York Cavalry destroyed the saltpeter works above Franklin, and the captured miners were taken to a prisoner-of-war camp at Old High Town above Monterey (Morton, 1910). The battles at Saltville in October and December 1864 temporarily suspended saltpeter operations at nearby Buchanan Cave. Nevertheless, during most of the war Confederate niter production kept pace with the growing demands of the military (Whisonant, 2001). Records from the Nitre and Mining Bureau reported that through 1864 Virginia produced 505,584¼ pounds of niter, accounting for about 29% of the total Confederate domestic supply (Schroeder-Lein, 1993).

After the war, cheap saltpeter produced from Chilean bird guano deposits began to flood the international markets, and the demand for domestic production disappeared. Then, around 1909, German scientist Fritz Haber developed a method for producing nitrates in the laboratory, relegating natural sources to the past.

References:

Faust, Burton, 1964, Saltpetre caves and Virginia history, in Douglas, Henry H., Caves of Virginia: Econo Print, Falls Church, Virginia.

Morton, Oren, 1910, A history of Pendleton County, West Virginia: Franklin, West Virginia.

Powers, J., 1981, Confederate niter production: National Speleological Society, Bulletin, v. 43.

Schroeder-Lein, G. R., 1993, Niter and Mining Bureau, in Current., R.N., editor, Encyclopedia of the Confederacy: Simon and Schuster, New York.

Whisonant, Robert C., 2001, Geology and history of Confederate saltpeter cave operations in western Virginia: Virginia Minerals, v. 47, no. 4.

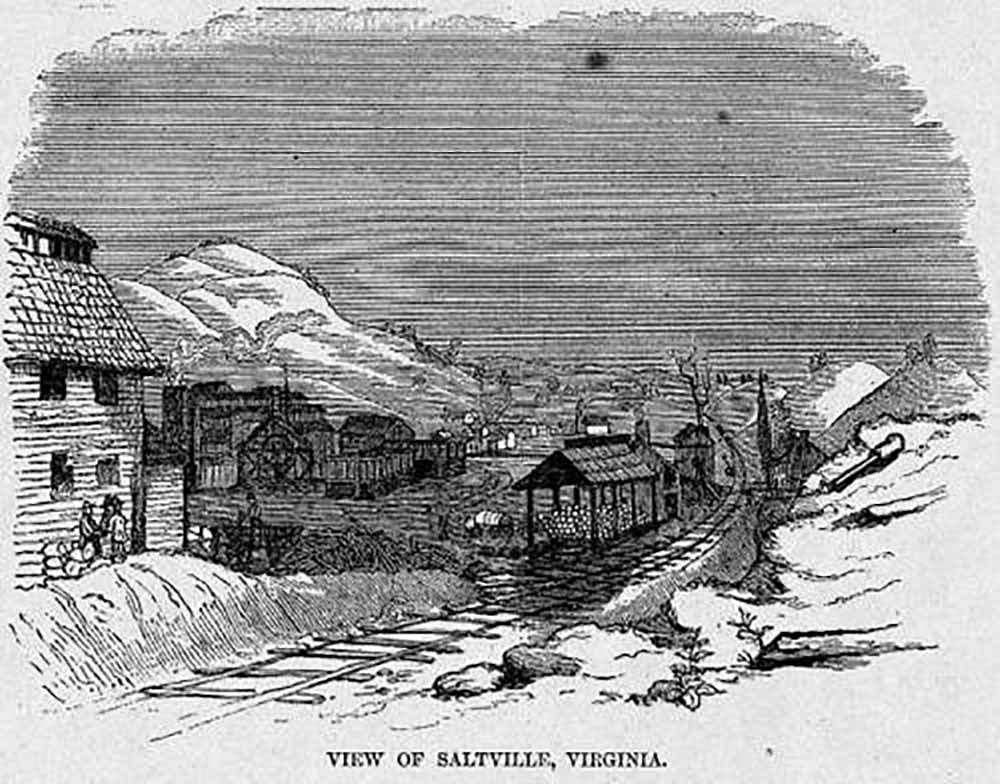

Salt was a particularly important commodity in the days before refrigeration, as it was the only practical method to preserve the huge amount of beef and pork necessary to feed the army and the civilian population, roughly nine million people in the South. It also was added to butter to stave off deterioration, it was used to pack eggs and cheese, and it was supplied as a nutrient to livestock. In addition, it was used to tan leather, a ubiquitous commodity which at the time had a multitude of everyday functions. It has been estimated that the average per capita consumption of salt in nineteenth century America was 50 pounds (Lonn, 1933). At the beginning of the Civil War, the United States imported 12 million bushels of salt annually, much of it going to the South.

Salt springs occur in the Valley and Ridge Province of southwestern Virginia. The salt is derived from the Mississippian-age Maccrady Formation, a sequence of shale, siltstone, limestone, dolostone, and evaporite minerals such as halite, anhydrite, and gypsum, all laid down across a mud-rich tidal flat on an ancient, arid coastline. After burial and lithification, these rocks were sheared and crushed along the Saltville Thrust Fault, a major structure that can be traced for hundreds of miles from northern Alabama to southwest Virginia (Whisonant, 1996). Migrating groundwater dissolved the salt, creating natural brine springs and ponds that attracted prehistoric animals such as mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths.

From Harper's Weekly, January 14, 1865

It is not known exactly when the first Europeans came upon the brine springs of the Holston Valley in southwestern Virginia, but by the 1750s a tract of land containing many of the springs had been granted to Charles Campbell, whose nephew, Arthur, began the first commercial development in 1782 (Whisonant, 1996). Brine was drawn up through wells and boiled off in large iron kettles. In 1795, William King built salt works on property adjoining Campbell’s and for the next several decades the two operations ran in competition. By 1842, production from six wells had reached 200,000 bushels annually (Whisonant, 1996). The 1840 census reported that Virginia produced 1,745,618 bushels that year. By 1850, Virginia salt production, primarily from Saltville and Kanawha (now in West Virginia), had reached 3,478,890 bushels per year, about 36% of the total domestic supply. In 1856, the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad was completed with a spur to Saltville.

By the fall of 1861, the Saltville works had been acquired by Stuart, Buchanan & Company, who managed the operation throughout the Civil War. Shortly after the war began, the company negotiated a contract with the Confederate government to supply the rebel army with 22,000 bushels per month (Whisonant, 1996). One of the partners, William A. Stuart, was the older brother of famous Confederate cavalryman General J.E.B. Stuart, whose wife and children spent much of the war at Saltville.

From the onset of the Civil War, the Union strategists undertook a concerted effort to neutralize southern salt works, including coastal operations in Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Alabama, along with inland facilities in Kentucky and Arkansas. The price of salt, which sold for as little as 17¢ per bushel before the war, shot up to over $8 in 1862 (Lonn, 1933). By the beginning of 1863, the wells at Saltville were the only remaining significant source of salt in the entire Confederacy, and production ramped up considerably. Prior to the war, the Saltville operations consisted of a single furnace and about seventy kettles; during its peak in 1864 there were thirty-eight furnaces operating upwards of 2,600 kettles, capable of producing 4,000,000 bushels annually (Whisonant, 1996).

The importance of Saltville was not lost on Union commanders, but forays against the salt wells in July and September 1863 and May 1864 never got close. However, on October 1, 1864, five thousand Union soldiers under General Stephen Burbridge managed to get to the outskirts of Saltville. The next day they attacked the outnumbered Confederate defenders, but were driven back and withdrew. Then, in December 1864, Union General George Stoneman’s cavalry raiding northward from Knoxville, Tennessee, ripped up the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad from Bristol to Wytheville, defeated weakened Confederate forces and overwhelmed the Saltville defenses, burning buildings and smashing kettles and kilns. Afterward, the Confederates made attempts to revive the operation, but by then the war was essentially over.

Salt production picked up slowly after the war. In 1893, the Holston Salt and Plaster Corporation was sold to a British company, Mathieson Alkali Works, and Saltville became a company town. Mathieson owned most of the nearby land and homes; it operated the utilities and paid the salaries of the police, ran company stores, built and staffed the hospital, and subsidized the school system (Tennessee Valley Perspective, 1973). Facilities expanded to include the world's largest dry ice plant and the second largest chlorine plant, but there were environmental problems. In July of 1970, the Mathieson Company, which for decades had dumped its effluent into the Holston River, announced that it would be unable to meet new EPA water pollution standards and closed the plant. Salt is still mined in Virginia today.

References:

Lonn, Ella, 1933, Salt as a factor in the Confederacy: Walter Neale, New York, 322 p.

Whisonant, Robert C., 1996, Geology and the Civil War in southwestern Virginia: the Smyth County salt works: Virginia Minerals, v. 42, no 3.

Tennessee Valley Perspective, Summer 1973: Tennessee Valley Authority.