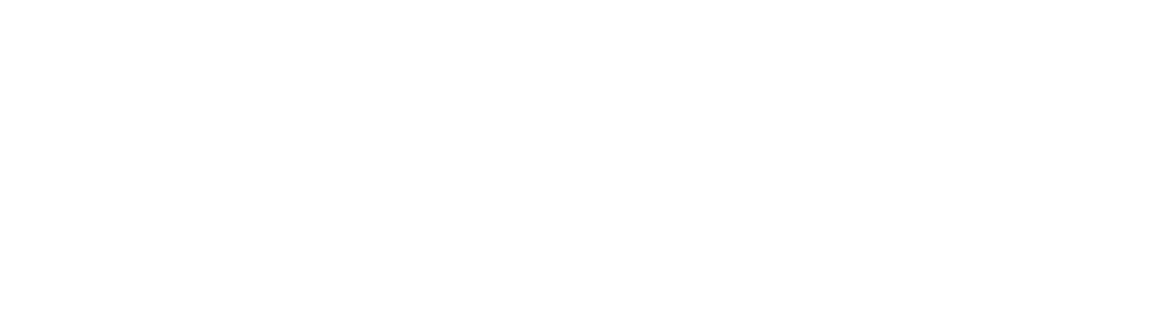

Hydraulic Fracturing (also known as hydrofracking, fracking, or fracking) has received considerable public attention due to drilling activity in the Marcellus Shale in the Appalachian region, the Barnett Shale in Texas, and the Bakken Shale in North Dakota and Montana. Hydraulic fracturing, along with horizontal drilling, has made previously-inaccessible natural gas and petroleum resources in tight or unconventional reservoirs producible in economic quantities. The application of these technologies has greatly expanded U.S. oil and natural gas production over the past ten years.

Data source: Energy Information Administration

Table of Contents

Use of Hydraulic Fracturing in Southwest Virginia

Drilling and Hydraulic Fracturing in other Parts of Virginia

What are Virginia Energy's Requirements to Protect Water Quality and the Environment?

Can Fracking in the New Shale Gas Plays be Conducted Safely in Virginia?

Much of Virginia's natural gas resources are found in unconventional” subsurface reservoirs, where the hydrocarbons are trapped in shale, coal or other tight rock formations with very low porosity and permeability. To access gas or oil resources in unconventional reservoirs, the rock formations must be stimulated or artificially fractured. Fracking, which dates back to the 1940s, uses pressurized liquids and/or gases such as nitrogen to stimulate or fracture rock formations to release the gas or oil. Sand is often pumped in with the fluids to help prop the fractures open. The composition and volume of fluids used depend largely on the regional geology, the chemical and mechanical properties of the reservoir rock, and the reservoir formation pressure.

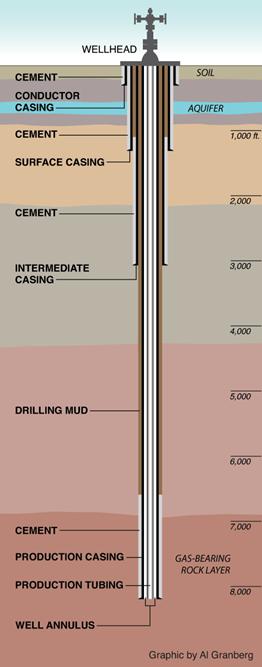

Especially in shale reservoirs, hydraulic fracturing is often combined with horizontal drilling. With this drilling method, the well is drilled vertically to a depth slightly above the target reservoir, and then directed horizontally and continued for several thousand feet within the reservoir. This technique exposes a longer section of the wellbore to the target formation than that of a strictly vertical well. Steel casing is then run to the bottom of the hole and secured in place with cement or packers. At this point, holes or perforations are created in the casing in the desired zones of production. Fluid and/or nitrogen gas, sometimes with sand proppant, are then pumped through the perforations under high pressure to generate small fractures in the shale reservoir. These fractures create the necessary conductivity for the hydrocarbons to flow into the wellbore at an economic flow rate.

Fracking Diagram

Use of Hydraulic Fracturing in Southwest Virginia

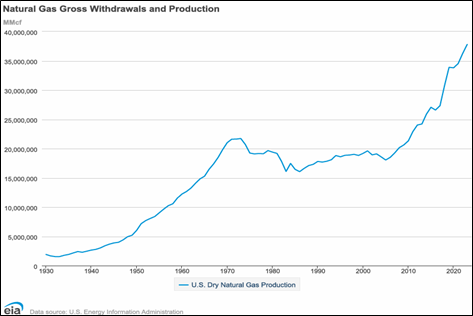

As of 2017, fracking has been utilized in approximately 2,100 wells producing from shale, sandstone and limestone formations in Southwest Virginia since the early to mid-1950s. In addition, more than 6,000 coalbed methane wells are producing from coal seams that have become fractured by post-mining subsidence or that have been fracked using water, chemicals and nitrogen with sand as the fracture proppant. This type of fracturing is known as a foam frac.” Due to the physical properties of the rock formations and the fairly low reservoir pressures in Southwest Virginia, large volumes of water are seldom used in the fracking process because water may hinder or block the flow of gas. Recent innovations have developed a 100% nitrogen frac with no liquid added, commonly called a dry” frac. Development of Southwest Virginia’s natural gas resources continues, with new wells being drilled and hydraulically fractured every year.

Map of Southwest VA natural gas Field

Most wells in Virginia are drilled using air and/or water to circulate well cuttings and lubricate the drilling bit. Any water used to drill through fresh water aquifers must meet or exceed regional water quality standards set by Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ). No modern drilling activities for gas or coalbed methane include the use of diesel fuel in the drilling or completion fluid.

Wellhead Tree and Nitrogen Trucks

Drilling and Hydraulic Fracturing in other Parts of Virginia

Currently the only producing gas and oil wells in Virginia are in the southwestern part of the Commonwealth. Exploratory wells were drilled in other parts of the state during the 20th century but all were plugged due to the absence of commercial quantities of hydrocarbons. The advent of horizontal drilling along with existing hydraulic fracturing technology renewed interest in some of these areas, including areas underlain by the Marcellus Shale in the western mountains and valleys, and the Mesozoic basins of eastern Virginia.

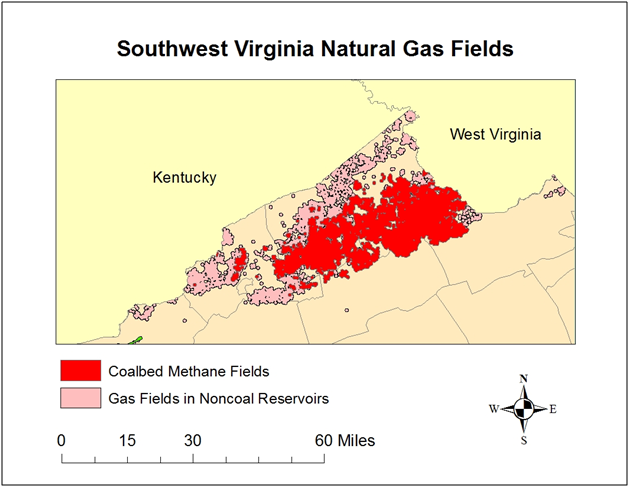

The Marcellus Shale in Virginia

The Marcellus is an organic-rich shale of Devonian age that is present beneath some of the mountains and valleys of western Virginia. The Marcellus is the primary target for recent horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, where it is thick and buried deeply beneath layers of younger sedimentary rock. In Virginia, the Marcellus is present in relatively shallow belts of folded and faulted rock. Due to this tectonic disturbance, much of the natural gas once present in the Marcellus has probably escaped. A recent study by the U.S. Geological Survey indicates that the Marcellus in that part of Virginia is thermally overmature, meaning that the shale was most likely heated to too high a temperature in the past to preserve economic quantities of gas or oil.Currently in Virginia, there are no wells producing natural gas from the Marcellus formation.

Marcellus Shale Map

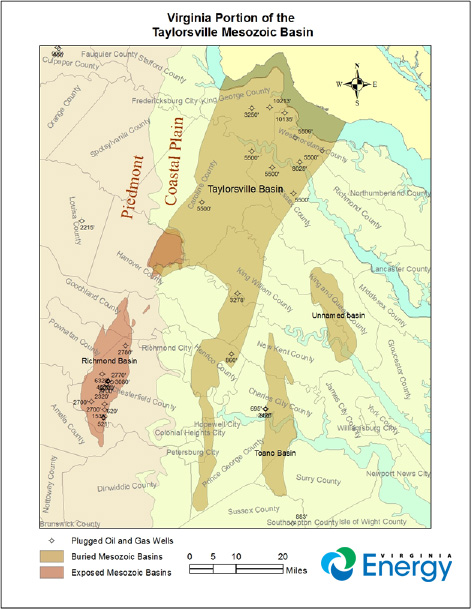

The Taylorsville Basin

The Taylorsville Basin is a Mesozoic-age sedimentary basin mostly concealed beneath younger sediments of Virginia’s Coastal Plain. The part of the basin beneath the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula was the subject of oil and gas exploration in the 20th century, with a dozen wells drilled between 1917 and 1992. All of the wells were plugged shortly after they were drilled, but a few showed indications of the presence of small quantities of natural gas and oil. One well that showed an indication of natural gas was hydraulically fractured in 1968, but the stimulation did not result in a commercially viable flow of gas so it was subsequently plugged.

Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Virginia Energy have signed an agreement on the coordinated review of the environmental impacts of potential permits for oil or gas drilling in the Coastal Plain that includes the Taylorsville Basin. The agencies have committed to ensuring a transparent process that includes a thorough environmental impact review and addresses all public comments. The agreement will help the agencies and the public focus on the distinctiveness and complexity of the Coastal Plain aquifer system, including the Potomac Aquifer, which supplies water for about half of Virginia's population for drinking, agricultural use and industrial use. Read the Memorandum of Agreement.

Taylorsville Mesozoic Basin Map

What are Virginia Energy's Requirements to Protect Water Quality and the Environment?

Virginia Energy's regulatory framework serves to allow for safe and environmentally responsible development and production of Virginia's natural gas resources. Virginia Energy's gas and oil permitting rules require the operator to complete site-specific assessments of the surface and underground conditions to be affected by drilling. These requirements are intended to ensure that well drilling and completion operations will not cause off-site disturbances, adversely affect the public, or contaminate surface water or groundwater. Virginia Energy will closely monitor stimulation methods and volumes of water used for well development, should new shale gas plays in Virginia prove viable. Virginia Energy will work closely with the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) to ensure that water withdrawals and disposal of produced fluids do not harm surface or ground waters and, depending on the volume of water used, whether any additional groundwater and surface withdrawal permits are required.

There have been no documented instances of surface water or groundwater degradation from fracking in Virginia. Surface water and groundwater protection is achieved through casing, cementing, and fluid management requirements that must be met when drilling and stimulating a well. As shown, multiple layers of steel pipe and cement extend through groundwater zones to prevent deep, often saline fluids from contaminating shallow, fresh groundwater.

Cross-section of multiple steel casings with cement between them.

Cemented casing is required at least 300 feet below the surface or 50 feet beneath the deepest known groundwater horizon, whichever is deeper. In the Tidewater region, special provisions are in place that require casing to be cemented minimum of 2,500 feet or 300 feet below the deepest fresh groundwater source. Typically, fracking occurs in formations that are at least 500 feet below fresh groundwater zones for coalbed methane wells and thousands of feet below fresh water zones for other types of gas wells. These requirements ensure protection of groundwater from contamination by drilling, fracking, or produced fluids.

Regulations require that each application for a permit must include a groundwater baseline sampling, analysis and monitoring plan. The groundwater monitoring program consists of initial baseline sampling and testing followed by subsequent sampling and testing after the well is drilled.

Graphic from ProPublica.org

Virginia Energy's Regulations also Protect Water Quality once Fracking Fluids Return to the Surface. Typically, only about 15-30% of injected fracking fluids return to the surface. Once returned to the surface, the fracking fluids must be stored in lined pits or approved tanks until permanent disposal. All gas well sites are closed loop" systems. No off-site disturbances or discharges are allowed. Drilling and fracking fluids are disposed in a permitted Class II EPA waste disposal well or are land applied after meeting regulatory requirements.

Virginia Energy's regulations also govern on-site road and gathering pipeline construction and operation. Construction must meet all erosion and sediment control, storm water, and reclamation requirements. All of these activities are covered under performance bonds.

Can Fracking in the New Shale Gas Plays be Conducted Safely in Virginia?

Virginia’s regulations are written so that all gas and oil development in the Commonwealth is conducted in a safe and environmentally responsible fashion. The fracking process has been used in the vast majority of producing wells in Southwest Virginia and is expected to continue. There have been no known water quality issues in Virginia directly associated with hydraulic fracturing. The EPA has performed multiple studies that have found no fresh water degradation from hydraulic fracturing activities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who has primary regulatory authority over natural gas and oil wells in Virginia?

Virginia Energy is the regulatory authority for statewide gas and oil permitting and operations. Interstate pipelines and gas storage fields are under the jurisdiction of the State Corporation Commission(SCC).

Special requirements apply to wells drilled in the Tidewater region. An application for a drilling permit must be accompanied by an Environmental Impact Assessment, which shall be reviewed by the Department of Environmental Quality, distributed to all appropriate state agencies, and be made available for public comment. Virginia Energy cannot issue a permit to drill until the recommendations of DEQ have been considered.

Do Virginia Energy inspectors have experience with shale gas wells?

Virginia Energy inspectors have experience with more than 2,100 vertical and horizontal shale gas wells. The main shale target formation in Virginia is the Lower Huron.

How often are the gas wells inspected by Virginia Energy?

Virginia Energy uses a risk-based inspection process. This means inspectors are present during the most critical stages of well development - site construction, drilling, cementing, fracking, and site reclamation. Once the well is completed and the site is stabilized, there is a substantially reduced risk of unintended impacts. At this point, gas company well tenders, on average, are visiting shale gas well sites once per week and coalbed methane wells two to three times per week to check production meters and well site conditions. Virginia Energy continues to inspect the site through the life of the well. Virginia law requires that companies immediately notify the Agency of any on-site or off-site problems related to the well, pipeline or facility.

Has Virginia received any permit applications to drill wells outside of Southwest Virginia?

There are no applications pending for wells to be drilled outside of the coalfield region of Southwest Virginia.

What does fracking fluid contain?

In both nitrogen-based and water-based fracking, additives are typically used as friction reducers, gelling agents, foaming agents, and antibacterials. Many of these ingredients are neutralized or diluted in the subsurface, and fracking operations do not result in concentrated volumes of chemical waste. The primary constituents of concern in fluids returned to the surface from fracking are chlorides and other salts. Additives remain a diluted constituent in the returned waters.

Concerns have been raised about the chemicals used in the hydraulic fracturing process. Do drilling companies have to identify the chemicals they are using?

A website has been established by the Ground Water Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC) for reporting materials used in hydraulic fracturing. Funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, this landmark, web-based national registry discloses the chemical additives used in the hydraulic fracturing process on a well-by-well basis, starting with wells drilled in 2011. Visit the website at www.fracfocus.org.

In 2016, Virginia Energy adopted regulations that require greater disclosure of chemicals used in stimulating oil and gas wells. Operators in Virginia are now required to submit a list of chemicals used during fracking and to report on Frac Focus. Learn More »

Is there a risk of radioactivity in the solids and water produced during the drilling and hydro-fracturing process?

Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials (NORMs) occur in low concentrations in most rock formations in Virginia, including host rocks of the gas and oil reservoirs. Very small concentrations of NORMs are commonly present in fluids produced from wells and rock cuttings returned to the surface. Risk of illness or injury from exposure is extremely low due to the very low concentrations present.

How are waters produced back during drilling and fracking handled?

- All waters and fluids produced during drilling and fracking must be captured in an approved and properly constructed pit or approved tank for temporary storage.

- Virginia regulations provide for the option of ground application of fluids if lab tests, conducted by an independent lab, show the fluids meet water quality standards. If the produced fluids do not meet quality standards, the operator is required to transport fluids to an approved Class II EPA waste disposal well or other properly permitted facility for permanent disposal.

- Regulations require that each application for a permit must include a groundwater baseline sampling, analysis and monitoring plan. The groundwater monitoring program consists of initial baseline sampling and testing followed by subsequent sampling and testing after the well is drilled.

- Water used to drill through fresh groundwater horizons is required to meet state water quality standards set by DEQ. This water can be drawn from a stream, a river, a water well, or it may be purchased from a Public Service Authority.

- The well casing/cementing program for each well is designed to protect ground water resources and coal seams below the surface. Virginia's casing program is a multi-casing and cementing program with the cement circulated to surface. This prevents contamination of groundwater, protects the coal resources, and isolates the gas production.

- The Virginia Gas and Oil Act and Regulations do not allow off-site impacts or discharges to surface waters.